As part of our 70th anniversary celebrations, we're sharing 70 stories from our arts community. Here is a selection of 10 works from our Permanent Collection of Saskatchewan artwork.

Heather Benning

Heather Benning

The Death of the Dollhouse: Fire #2, 2013

Kodak Endura digital C-print

The Dollhouse was created in 2007, during a Saskatchewan Arts Board artist-in-residence program at Redvers. Heather renovated the wooden house into a life-sized dollhouse, complete with vintage furnishings and a transparent wall on one side, so you could see the interior. In October 2012, the house began to show its age; the foundation was compromised. The house was meant to stand as long as it remained safe. In March 2013, The Dollhouse met its death with fire.

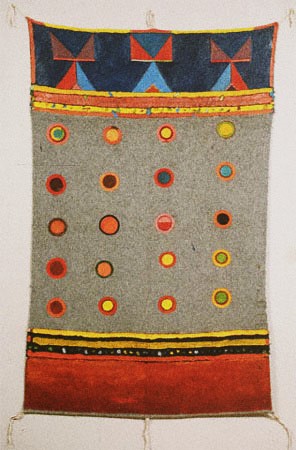

Bob Boyer

A Smallpox Issue, 1983

blanket, oil, rawhide

Wally Dion

Starblanket, 2006

printed circuit board, brass wire, acrylic paint, copper tubing

Wally Dion’s Starblanket is a First Nations star blanket fashioned from computer circuit boards. Dion recycles first world waste, using an iconic star pattern that references traditional Plains First Nations quilts and blankets. Playing with the concept of time and tradition, the piece stimulates discussion of how traditions are valued and interpreted within modern society. Its use of material and symbolism alludes to systems of connections and communication. The modern circuitry offers an updated representation of longstanding social networks, while also speaking to empowerment through technology within First Nations communities.

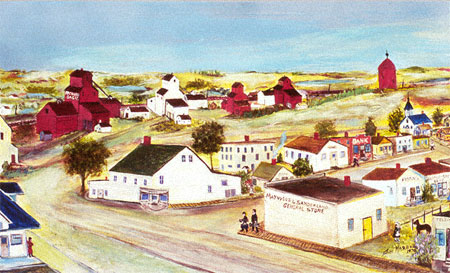

Ann Harbuz

Ann Harbuz

Richard Town, 1976

acrylic, ink on Masonite

Ann Harbuz spent much of her adult life in North Battleford. She did not start painting until she was in her 60s, but in a flurry of activity spanning 23 years, she produced more than 1,000 landscapes, still lifes and portraits. She was a self-taught artist; her works show little regard for formal or technical considerations and have been described as having a “child-like simplicity.” Instead, they focus on content and subject matter, such as home, family and nature. She used all kinds of media: canvas, paper, velvet, glass and plastic, as well as watercolour, oil, acrylic, pen, ink and even coffee and latex.

Her goal was to supplement her family’s photographic archive, and her work related to what she observed in her local environment, as well as to her childhood memories and Ukrainian heritage. Scenes of everyday life, chores, farms and celebrations feature prominently in her paintings, which represent a form of visual diary and function as “social landscapes.” The stories she tells celebrate the strength and ingenuity of pioneer women. Harbuz passed away in 1989.

Kaija Sanelma Harris

Framed Series No. 2, 2006

Swedish carpet wool, Canadian yarn, cotton, synthetic yarn

Kaija Sanelma Harris was born in Finland but has lived in Saskatoon long enough to think of it as home. Fibre work was an important part of Scandinavian culture when Harris was young. There was value attached to creating works which were functional, beautiful and unique.

While she has used many different textile techniques in her work, Harris chose weaving as her main medium, exploring double weaves in the past two decades. The visual impact of her tapestries is accomplished by combining imagery, structure, materials and finishing methods that influence the surface.

Framed Series No. 2 is part of a series called Colour Maps and has its roots in a visit Harris made to Northern Lake in Prince Albert National Park more than ten years ago. While there, she had many walks in the woody area by the shoreline. “It was a treat for the eye,” she said. Back in Saskatoon, she recorded her experience in yarn and began creating “colour maps” of other landscapes from memory.

Dorothy Knowles

Dorothy Knowles

Fields in Summer, 1969

oil, charcoal on canvas

Dorothy Knowles initially had no plans to become an artist, studying biology at the University of Saskatchewan. When she graduated, a friend convinced her to enroll in a summer painting course at Emma Lake. She was hooked. She continued her education in painting at the University of Saskatchewan, going on to study in London, England. She married fellow renowned Saskatoon painter William Perehudoff in 1953.

Knowles is best known for her landscape paintings and has been referred to as “the matriarch of painting in Saskatchewan.” Weather permitting, she worked outdoors, using a van as a portable studio, at times producing finished paintings and at others sketches and photographs she later used in the studio. She once used a car breakdown on a road trip as an opportunity to whip out her watercolours and capture a splendid sunset.

Prairie valleys and the prairie and parkland near Saskatoon have been a recurrent theme in her art. American critic Clement Greenburg wrote, “…she was the only landscape painter I came across…whose work tended towards the monumental in an authentic way,” noting that her work was more successful than that of The Group of Seven in this regard.

Clint Neufeld

Ten Thousandths Over, 2008

ceramic, steel, found objects

Clint Neufeld’s sculptures involve a play between contradictory forms, materials and purposes. He works with the most Saskatchewan of forms: engines, excavating buckets and other mechanical devices. Yet, unlike the real objects, his sculptures are not made with industrial materials; they are handcrafted from substances such as porcelain and wax.

Each sculpture starts out as a real engine. Neufeld tracks down missing parts and then cleans and disassembles the entire thing and casts each piece in clay, using a process called slip molding. Then, he glazes the individual parts with traditional tea-set glazes and patterns, hardens them in a kiln and reassembles the final engine for display.

The title, Ten Thousandths Over, refers to the standard to which a rebuilt engine is initially bored to, 10/1000 of an inch over the original cylinder size. This engine has been constructed from ceramic and decorated in blue and white in the tradition of Delft china. The engine rests on a metal cart, which resembles a tea service but also recalls the carts used by mechanics to run engines to different locations for diagnostics.

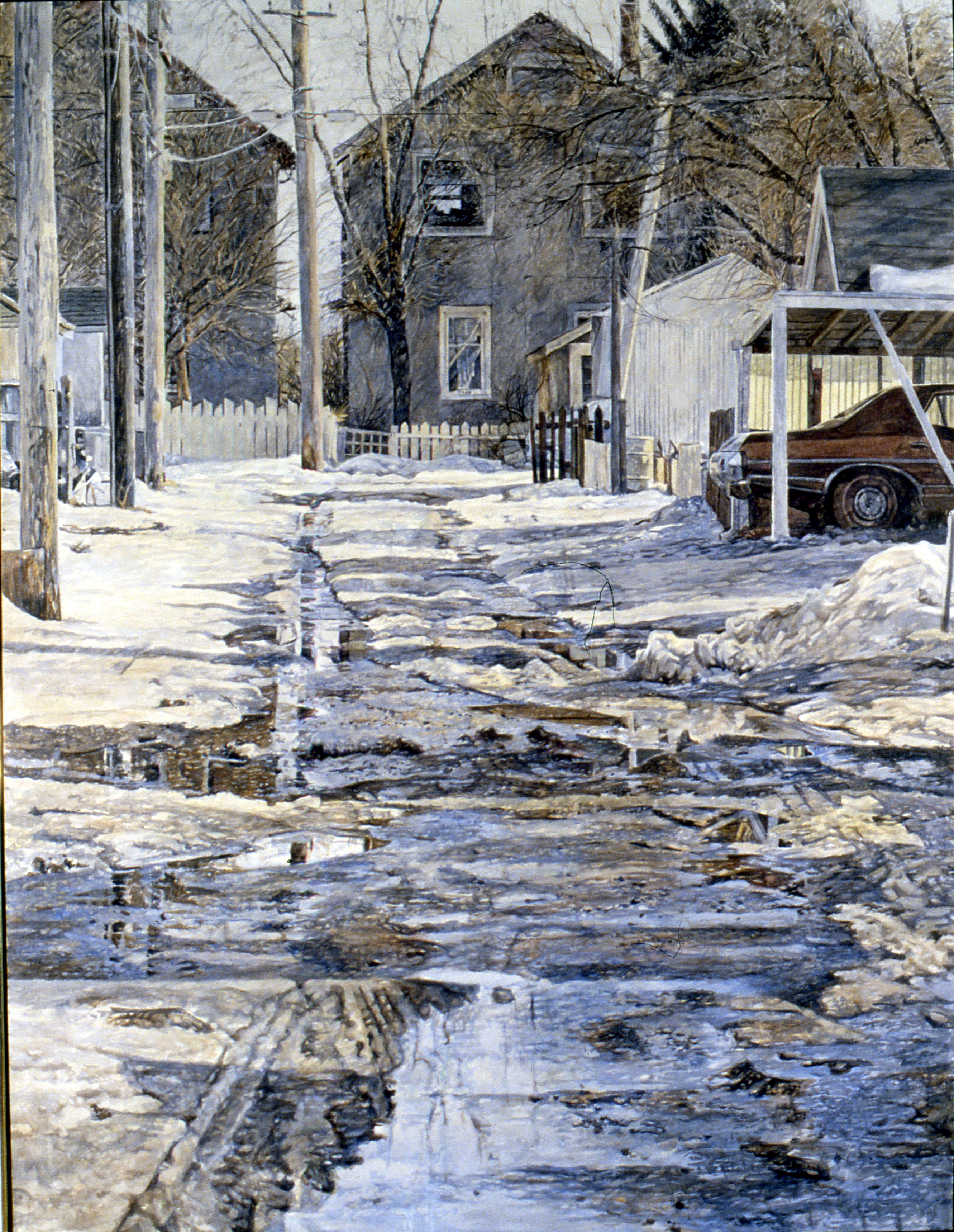

Wilf Perreault

Carport, 1980

acrylic on canvas

Wilf Perreault’s paintings depict ordinary aspects of the urban landscape in an extraordinary manner. He found his muse in a back alley, where he had stopped to look at the reflection of sky and buildings in a puddle. Looking up, he saw a hidden cityscape in the back lane that captured his imagination.

In a 1990 interview, he said, “I found the alleys more intimate than the front streets. They’re also more interesting. There is an absence of people but there are the tracks that people leave behind.” Perreault also said that the great thing about an alley is that things are allowed to grow in a natural, haphazard way. He is also one of the only people who appreciates the water-filled sink holes that appear in back alleys in the spring, because he loves to paint the sky reflected in them.

While Perreault has continued to paint back alleys since the 1970s, he hasn’t gotten tired of it. In a 2016 interview, he said, “I play with the same subject, but somehow it’s always a different experience.”

Lionel Peyachew

Hockey Player, 1998

oil on canvas

Well known as a sculptor, Cree artist Lionel Peyachew has created some important public sculptures over the last ten years, most recently the monument to Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women located outside the Saskatoon Police Station in 2017. A full time associate professor of Indian fine arts at First Nations University of Canada, Peyachew is also an accomplished painter who often combines traditional Indigenous symbols and historic images with contemporary subjects. Hockey Player is a portrait of Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux Chief Sitting Bull. Peyachew transports the iconic warrior into a hockey changeroom where he cheekily wears a Chicago Blackhawks jersey, with moccasins tucked under the bench and a medicine bag on the shelf.