-

Wynona Mulcaster, Trees, circa 1954, oil on masonite

Wynona Mulcaster was born in Prince Albert. She was interested in horses and made them the subjects of her early drawings. She worked mainly in acrylics on canvas or paper and is known for prairie landscapes. Mulcaster studied art under Ernest Lindner from 1935-45. In the late 1930s, she helped to establish the Emma Lake Artists' Workshops. She spent several years as an art teacher to school children in Prince Albert and rural Saskatchewan, taught art at the Saskatchewan Teachers' College in Saskatoon and was later a professor of visual art at the University of Saskatchewan. Her work has been widely exhibited in Canada and is represented in many collections, such as the Canada Council Art Bank, the MacKenzie Art Gallery, the Remai Modern and the Glenbow Museum. Wynona Mulcaster passed away in 2016.

![1 wynona mulcaster trees 1 wynona mulcaster trees]()

Wynona Mulcaster, Trees, circa 1954, oil on masonite

Wynona Mulcaster was born in Prince Albert. She was interested in horses and made them the subjects of her early drawings. She worked mainly in acrylics on canvas or paper and is known for prairie landscapes. Mulcaster studied art under Ernest Lindner from 1935-45. In the late 1930s, she helped to establish the Emma Lake Artists' Workshops. She spent several years as an art teacher to school children in Prince Albert and rural Saskatchewan, taught art at the Saskatchewan Teachers' College in Saskatoon and was later a professor of visual art at the University of Saskatchewan. Her work has been widely exhibited in Canada and is represented in many collections, such as the Canada Council Art Bank, the MacKenzie Art Gallery, the Remai Modern and the Glenbow Museum. Wynona Mulcaster passed away in 2016.

-

Ernest Lindner, Cedar Bark, 1969, watercolour, graphite on paper

Born in Austria in 1897, Ernest Lindner immigrated to Saskatoon in 1926, first working as a farm labourer, then becoming a self-taught commercial artist. He soon became recognized locally and nationally. Best known for his works in watercolour and pencil, he also produced linocut and wood-block prints and studied etching and lithography. He was one of the first members of the Saskatchewan Arts Board and influenced the University of Saskatchewan to run its annual Emma Lake Artists' Workshops. Some of the prominent Modernist painters of New York were guests at the workshops in the late 1950s and early 1960s and were influenced by Lindner's style. His paintings were exhibited across Canada and in Europe, and his work is represented in collections including the Academy of Applied Art (Vienna), Grant Central Galleries (New York City), the Royal Ontario Museum, the Art Gallery of Ontario and the National Gallery of Canada. Ernest Lindner passed away in 1988. In 2007 the Saskatchewan government designated his studio at Emma Lake as a provincial heritage property.

![2 lindner cedar bark 1969 2 lindner cedar bark 1969]()

Ernest Lindner, Cedar Bark, 1969, watercolour, graphite on paper

Born in Austria in 1897, Ernest Lindner immigrated to Saskatoon in 1926, first working as a farm labourer, then becoming a self-taught commercial artist. He soon became recognized locally and nationally. Best known for his works in watercolour and pencil, he also produced linocut and wood-block prints and studied etching and lithography. He was one of the first members of the Saskatchewan Arts Board and influenced the University of Saskatchewan to run its annual Emma Lake Artists' Workshops. Some of the prominent Modernist painters of New York were guests at the workshops in the late 1950s and early 1960s and were influenced by Lindner's style. His paintings were exhibited across Canada and in Europe, and his work is represented in collections including the Academy of Applied Art (Vienna), Grant Central Galleries (New York City), the Royal Ontario Museum, the Art Gallery of Ontario and the National Gallery of Canada. Ernest Lindner passed away in 1988. In 2007 the Saskatchewan government designated his studio at Emma Lake as a provincial heritage property.

-

Martha Cole, Scots Pine 2, 2009, digital image, ink, cotton, Setacolor fabric paints, assorted threads on unbleached cotton with polyester batting

Martha Cole was born in 1946, in Regina, Saskatchewan. She decided she wanted to be an artist when she was 14 years old. In the mid-1960s she received grants from the Saskatchewan Arts Board to study fine art at the University of Washington. In the early 70s she received a bachelor of education degree from the University of Toronto and taught art to high school students for three years. Frustrated by the high cost of living she decided to return to Saskatchewan. In 1978 Cole bought an old church in the village of Disley, 50 kilometres northeast of Regina, and made it her home and studio space. There, she continues to work on her fabric pieces, using techniques including sewing, quilting, and embroidery to create pieces inspired by the Saskatchewan landscape. Scots Pine 2 was created as part Interdependencies, a series of beautifully detailed portraits of the natural world. Embracing new technology, Cole took digital images of trees, rocks and plants, altered the images in Photoshop then transferred them onto cotton and silk using commercial printers. After printing, Cole embellished detail with acrylic based fabric paints, extensive machine stitching, colored pencils and appliqué. They are then quilted. This time-consuming process Cole painstakingly applied to the creation of the hangings reflects her passion for the natural world. "We are part of that natural order of things. At some level we have within us a deep understanding of this order of complexity beyond our rational comprehension. By using this kind of subject matter, I hope to make myself and others more comfortable in this very complex and very changing world while understanding our embeddedness within it." - Martha Cole

![3 cole view1 scots pine 2 3 cole view1 scots pine 2]()

Martha Cole, Scots Pine 2, 2009, digital image, ink, cotton, Setacolor fabric paints, assorted threads on unbleached cotton with polyester batting

Martha Cole was born in 1946, in Regina, Saskatchewan. She decided she wanted to be an artist when she was 14 years old. In the mid-1960s she received grants from the Saskatchewan Arts Board to study fine art at the University of Washington. In the early 70s she received a bachelor of education degree from the University of Toronto and taught art to high school students for three years. Frustrated by the high cost of living she decided to return to Saskatchewan. In 1978 Cole bought an old church in the village of Disley, 50 kilometres northeast of Regina, and made it her home and studio space. There, she continues to work on her fabric pieces, using techniques including sewing, quilting, and embroidery to create pieces inspired by the Saskatchewan landscape. Scots Pine 2 was created as part Interdependencies, a series of beautifully detailed portraits of the natural world. Embracing new technology, Cole took digital images of trees, rocks and plants, altered the images in Photoshop then transferred them onto cotton and silk using commercial printers. After printing, Cole embellished detail with acrylic based fabric paints, extensive machine stitching, colored pencils and appliqué. They are then quilted. This time-consuming process Cole painstakingly applied to the creation of the hangings reflects her passion for the natural world. "We are part of that natural order of things. At some level we have within us a deep understanding of this order of complexity beyond our rational comprehension. By using this kind of subject matter, I hope to make myself and others more comfortable in this very complex and very changing world while understanding our embeddedness within it." - Martha Cole

-

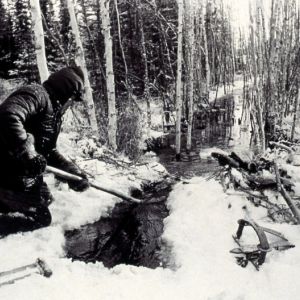

Dave O’Hara, Jonas and Beaverlodge, December 1979, 1979, silver print

David O'Hara was born in 1947 in London, Ontario. He studied photography in Toronto, Ontario at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute, graduating in 1971. O'Hara later moved to Saskatchewan and first worked with children in Regina before heading north and settling in La Loche. One series of his black-and-white photographs documents an elder, Jonas Clark, as he participates in the fishing and trapping life of his northern community. O'Hara's photographs have been exhibited in Regina and Saskatoon, including at the Art Gallery of Regina and at The Photographers' Gallery (now PAVED Arts). His work is in the collection of PAVED Arts and was exhibited there with the work of other artists in the collection in 2004. David O'Hara died in 1984 in a canoe accident at the age of 36. The Dave O'Hara Community Library in La Loche is named in his honour.

![4 ohara jonas and beaverlodge 4 ohara jonas and beaverlodge]()

Dave O’Hara, Jonas and Beaverlodge, December 1979, 1979, silver print

David O'Hara was born in 1947 in London, Ontario. He studied photography in Toronto, Ontario at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute, graduating in 1971. O'Hara later moved to Saskatchewan and first worked with children in Regina before heading north and settling in La Loche. One series of his black-and-white photographs documents an elder, Jonas Clark, as he participates in the fishing and trapping life of his northern community. O'Hara's photographs have been exhibited in Regina and Saskatoon, including at the Art Gallery of Regina and at The Photographers' Gallery (now PAVED Arts). His work is in the collection of PAVED Arts and was exhibited there with the work of other artists in the collection in 2004. David O'Hara died in 1984 in a canoe accident at the age of 36. The Dave O'Hara Community Library in La Loche is named in his honour.

-

Hans Herold, Moss and Rotting Birches, 1968, acrylic on canvas

Hans Herold was born in 1925 on his family’s 200-year-old farm in Germany, and as a young man he moved to Munich to study art. He came to Saskatchewan in 1957, first working on a farm, then as a miner in Uranium City. Eventually Herold settled in Saskatoon, making a living as a house painter while becoming heavily involved in the arts community. Largely self taught, his landscape paintings, scenes of prairie skies, lakes, and fields are recognizable for their delicate, impressionistic style. Herold had his first solo exhibition in 1965 at Saskatoon's Mendel Art Gallery. "I have to paint for myself. That is why I am never worried about painting what other people like. Some people may feel my landscapes are too abstract, but I have to paint what I like." Hans Herold, StarPhoenix, 1977. In 1987, Herold moved to Vancouver Island and began painting his new surroundings, including scenes of the Pacific ocean and lush flower gardens. Herold's work is represented in many collections throughout Canada, including the Remai Modern, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Canada Council Art Bank, Winnipeg Art Gallery, and Hamilton Art Gallery. Herold died in 2011 in Duncan, British Columbia. He was 85.

![5 hans harold moss and rotting birches 5 hans harold moss and rotting birches]()

Hans Herold, Moss and Rotting Birches, 1968, acrylic on canvas

Hans Herold was born in 1925 on his family’s 200-year-old farm in Germany, and as a young man he moved to Munich to study art. He came to Saskatchewan in 1957, first working on a farm, then as a miner in Uranium City. Eventually Herold settled in Saskatoon, making a living as a house painter while becoming heavily involved in the arts community. Largely self taught, his landscape paintings, scenes of prairie skies, lakes, and fields are recognizable for their delicate, impressionistic style. Herold had his first solo exhibition in 1965 at Saskatoon's Mendel Art Gallery. "I have to paint for myself. That is why I am never worried about painting what other people like. Some people may feel my landscapes are too abstract, but I have to paint what I like." Hans Herold, StarPhoenix, 1977. In 1987, Herold moved to Vancouver Island and began painting his new surroundings, including scenes of the Pacific ocean and lush flower gardens. Herold's work is represented in many collections throughout Canada, including the Remai Modern, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Canada Council Art Bank, Winnipeg Art Gallery, and Hamilton Art Gallery. Herold died in 2011 in Duncan, British Columbia. He was 85.

-

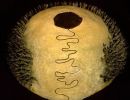

Angelique Merasty, Untitled, ND, birch bark

Angelique Merasty was born in Beaver Lake, Saskatchewan in 1924. She learned the art of birchbark biting from her mother, Susan Ballantyne, who was very respected for her traditional designs. Birchbark biting is known as wigwas mamacenawejegan in Ojibwa and is one of the oldest Indigenous art forms. Merasty’s designs have developed from geometric and flower patterns to more complex insects and animals. Though the practice of birch bark biting was once a common form of art and entertainment in many communities, fewer artists are learning the skill. Merasty was recognized and respected as a senior artist in this medium. Her work has been exhibited widely, including at the Museum of Man and Nature (now the Manitoba Museum, Winnipeg, 1980), and the Thunder Bay National Exhibition Centre and Centre for Indian Art (1983). Merasty passed away in Saskatoon in 1996.

![6 angelique merasty untitled 6 angelique merasty untitled]()

Angelique Merasty, Untitled, ND, birch bark

Angelique Merasty was born in Beaver Lake, Saskatchewan in 1924. She learned the art of birchbark biting from her mother, Susan Ballantyne, who was very respected for her traditional designs. Birchbark biting is known as wigwas mamacenawejegan in Ojibwa and is one of the oldest Indigenous art forms. Merasty’s designs have developed from geometric and flower patterns to more complex insects and animals. Though the practice of birch bark biting was once a common form of art and entertainment in many communities, fewer artists are learning the skill. Merasty was recognized and respected as a senior artist in this medium. Her work has been exhibited widely, including at the Museum of Man and Nature (now the Manitoba Museum, Winnipeg, 1980), and the Thunder Bay National Exhibition Centre and Centre for Indian Art (1983). Merasty passed away in Saskatoon in 1996.

-

Lorne Beug, Earth Section with Trees, 1973, coloured clays and glazes

Born in Regina, Lorne Beug first went to university to focus on anthropology and psychology, later studying ceramics under such artists as Joe Fafard and Marilyn Levine. His study of anthropology, archaeology, geology and psychoanalysis has had a great influence on his art, which draws on themes of history, urban life and prairie landscape. Beug has gradually shifted away from clay over the years, incorporating a variety of media into his art and working in photo collage, faux marbling, mosaic mapping and mixed-media sculpture. Some of his commissions include a ceramic mural for the City of Regina Fieldhouse and a tile floor for the Riddell Centre at the University of Regina. His work can also be found in the collections of the Remai Modern, MacKenzie Art Gallery, Dunlop Art Gallery, Glenbow Museum, Memorial University and the Canada Council Art Bank. He lives in Regina, where he continues to make art.

![7 lorne beug earth section with trees 7 lorne beug earth section with trees]()

Lorne Beug, Earth Section with Trees, 1973, coloured clays and glazes

Born in Regina, Lorne Beug first went to university to focus on anthropology and psychology, later studying ceramics under such artists as Joe Fafard and Marilyn Levine. His study of anthropology, archaeology, geology and psychoanalysis has had a great influence on his art, which draws on themes of history, urban life and prairie landscape. Beug has gradually shifted away from clay over the years, incorporating a variety of media into his art and working in photo collage, faux marbling, mosaic mapping and mixed-media sculpture. Some of his commissions include a ceramic mural for the City of Regina Fieldhouse and a tile floor for the Riddell Centre at the University of Regina. His work can also be found in the collections of the Remai Modern, MacKenzie Art Gallery, Dunlop Art Gallery, Glenbow Museum, Memorial University and the Canada Council Art Bank. He lives in Regina, where he continues to make art.

-

Catherine Blackburn, As We Dance, 2016, beads on canvas

Catherine Blackburn was born in Patuanak Saskatchewan, of Dene and European ancestry and is a member of the English River First Nation. She completed a bachelor of fine art from the University of Saskatchewan in 2007. She is a multidisciplinary artist and jeweller; whose common themes address Canada's colonial past that are often prompted by personal narratives. Her art merges contemporary concepts with elements of traditional Dene culture that create dialogue between traditional art forms and new interpretations of them. Her work has exhibited in notable national and international exhibitions and fashion runways including Àbadakone, National Gallery of Canada, Santa Fe Haute Couture Fashion Show, Niigaanikwewag (2nd iteration), Art Gallery of Mississauga, and Art Encounters on the Edge, Bonavista Biennale, Newfoundland. She has received numerous grants and awards for her work, including the Saskatchewan RBC Emerging Artt Award, the Melissa Levin Emerging Artist Award, a publication in Vogue online magazine, as well as her inclusion on the 2019 Sobey Art Award longlist. Her pieces have been purchased into numerous public and private collections across Canada. Her work draws attention locally and nationally for its cultural sensitivity, accomplished technical skill and strong conceptual viewpoints. Catherine Blackburn lives in Thornhill, British Columbia where she continues to create art.

![8 catherine blackburn as we dance 8 catherine blackburn as we dance]()

Catherine Blackburn, As We Dance, 2016, beads on canvas

Catherine Blackburn was born in Patuanak Saskatchewan, of Dene and European ancestry and is a member of the English River First Nation. She completed a bachelor of fine art from the University of Saskatchewan in 2007. She is a multidisciplinary artist and jeweller; whose common themes address Canada's colonial past that are often prompted by personal narratives. Her art merges contemporary concepts with elements of traditional Dene culture that create dialogue between traditional art forms and new interpretations of them. Her work has exhibited in notable national and international exhibitions and fashion runways including Àbadakone, National Gallery of Canada, Santa Fe Haute Couture Fashion Show, Niigaanikwewag (2nd iteration), Art Gallery of Mississauga, and Art Encounters on the Edge, Bonavista Biennale, Newfoundland. She has received numerous grants and awards for her work, including the Saskatchewan RBC Emerging Artt Award, the Melissa Levin Emerging Artist Award, a publication in Vogue online magazine, as well as her inclusion on the 2019 Sobey Art Award longlist. Her pieces have been purchased into numerous public and private collections across Canada. Her work draws attention locally and nationally for its cultural sensitivity, accomplished technical skill and strong conceptual viewpoints. Catherine Blackburn lives in Thornhill, British Columbia where she continues to create art.

-

Sheila Archer, Eye of the Muskeg, 1989, clay, gouache

Born in Regina in 1963 Sheila Archer attended Emily Carr University (1981-83) and the University of Saskatchewan (1983-87). Archer lived and worked in Moose Jaw during the winter, during the summer lived outdoors in northern Saskatchewan, gathering ideas for her studio. "Eye of the Muskeg" was inspired by a flight over the Churchill River on-route to the Foster River in northern Saskatchewan. Archer worked as a canoe guide in northern Saskatchewan for over 20 years and often traveled by float plane. She became interested in how the geometry of prairie landscape observed from the air contrasted with the natural forms of rivers and forests, the boreal forest of Saskatchewan's north is largely unchanged by human hand. This contrast of landscape became Archer's focus in her art. "When I first started spending time in northern Saskatchewan I was travelling by canoe, using my camera to record what I was seeing… it took 3 years of goingup to the Churchill before an answer came to me; a way of turning what I was seeing there into a sculptural form." --Sheila Archer, studio interviews January 1990. Sheila Archer now lives in Sayward, British Columbia.

![91 archer eye of the muskeg 91 archer eye of the muskeg]()

Sheila Archer, Eye of the Muskeg, 1989, clay, gouache

Born in Regina in 1963 Sheila Archer attended Emily Carr University (1981-83) and the University of Saskatchewan (1983-87). Archer lived and worked in Moose Jaw during the winter, during the summer lived outdoors in northern Saskatchewan, gathering ideas for her studio. "Eye of the Muskeg" was inspired by a flight over the Churchill River on-route to the Foster River in northern Saskatchewan. Archer worked as a canoe guide in northern Saskatchewan for over 20 years and often traveled by float plane. She became interested in how the geometry of prairie landscape observed from the air contrasted with the natural forms of rivers and forests, the boreal forest of Saskatchewan's north is largely unchanged by human hand. This contrast of landscape became Archer's focus in her art. "When I first started spending time in northern Saskatchewan I was travelling by canoe, using my camera to record what I was seeing… it took 3 years of goingup to the Churchill before an answer came to me; a way of turning what I was seeing there into a sculptural form." --Sheila Archer, studio interviews January 1990. Sheila Archer now lives in Sayward, British Columbia.

-

Louise Cook, Forest I, 2003, acrylic on canvas

Louise Cook was born in 1943 in Fir Ridge, Saskatchewan. She studied at the University of Saskatchewan, under Otto Rogers, Mina Forsythe, and Bob Christie. She also attended the Emma Lake Summer Workshops since 1988 where she studied with William Perehudoff, Dorothy Knowles, Terry Fenton, Douglas Haynes and Kenneth Noland to name a few. An avid birder, Cook regularly travels north participating in bird counts for Nature Saskatchewan. She always travels with a watercolour kit to complete small studies as sources for larger paintings. Her paintings reflect her intimate knowledge of the lakes, rivers, forests and valleys of Saskatchewan. She is most interested in the chaos of nature rather than the picturesque. Forest I captures the tangle of decaying trees along the edge of a muskeg swamp. Louise Cook's first show was at the Mendel art gallery in 1973 entitled "Three Sisters Show." She has exhibited in Saskatoon, Regina, Calgary, Edmonton and Vancover. Her solo exhibition "Saskatchewan Paintings" at the Legislature Building in Regina was visited by Prince Edward Earl of Wessex. Louise Cook continues to paint from her studio in Saskatoon. In 2019 and 2020 she donated 9 paintings to the collection, including Forest I.

![92 cook forest i 92 cook forest i]()

Louise Cook, Forest I, 2003, acrylic on canvas

Louise Cook was born in 1943 in Fir Ridge, Saskatchewan. She studied at the University of Saskatchewan, under Otto Rogers, Mina Forsythe, and Bob Christie. She also attended the Emma Lake Summer Workshops since 1988 where she studied with William Perehudoff, Dorothy Knowles, Terry Fenton, Douglas Haynes and Kenneth Noland to name a few. An avid birder, Cook regularly travels north participating in bird counts for Nature Saskatchewan. She always travels with a watercolour kit to complete small studies as sources for larger paintings. Her paintings reflect her intimate knowledge of the lakes, rivers, forests and valleys of Saskatchewan. She is most interested in the chaos of nature rather than the picturesque. Forest I captures the tangle of decaying trees along the edge of a muskeg swamp. Louise Cook's first show was at the Mendel art gallery in 1973 entitled "Three Sisters Show." She has exhibited in Saskatoon, Regina, Calgary, Edmonton and Vancover. Her solo exhibition "Saskatchewan Paintings" at the Legislature Building in Regina was visited by Prince Edward Earl of Wessex. Louise Cook continues to paint from her studio in Saskatoon. In 2019 and 2020 she donated 9 paintings to the collection, including Forest I.

-

William Laczko, Bird Tree, 1983, wood, metal, plastic, paint, graphite

William Laczko was born in St. Brieux in 1927. Married in 1949, William and his wife Elizabeth bought land to farm in Saskatchewan. During the winter they traveled to Ontario where William worked at the Red Lake Gold Mine, leading to 10 years living in Ontario before returning to Saskatchewan permanently in 1961. On a trip to Fort Smith, North West Territories to visit family, they saw carving by Wilf Neill. They loved his work so much they purchased a carving of a ptarmigan to bring home. The trip inspired him to take up wood carving when he returned home. It began as a hobby, carving birds, fish and human figures for family and friends. He later sold some of his work and exhibited in local shows. His carvings are part of many private folk art collections. William and Elizabeth continued to farm until 1989 when they moved into St. Brieux. William Laczko passed away in 1995.

![93 william laczko bird tree 93 william laczko bird tree]()

William Laczko, Bird Tree, 1983, wood, metal, plastic, paint, graphite

William Laczko was born in St. Brieux in 1927. Married in 1949, William and his wife Elizabeth bought land to farm in Saskatchewan. During the winter they traveled to Ontario where William worked at the Red Lake Gold Mine, leading to 10 years living in Ontario before returning to Saskatchewan permanently in 1961. On a trip to Fort Smith, North West Territories to visit family, they saw carving by Wilf Neill. They loved his work so much they purchased a carving of a ptarmigan to bring home. The trip inspired him to take up wood carving when he returned home. It began as a hobby, carving birds, fish and human figures for family and friends. He later sold some of his work and exhibited in local shows. His carvings are part of many private folk art collections. William and Elizabeth continued to farm until 1989 when they moved into St. Brieux. William Laczko passed away in 1995.

Curatorial Statement

When people think of Saskatchewan landscape, the prairie is what comes to mind. There is no doubt the expansive sky and vast plains of farmland are at the core of our identity and culture; however, for anyone who lives in this province, there is an awareness this is only part of the story. The boreal forest covers over half of Saskatchewan. It is home to cities, towns, rural and Indigenous communities, farms, cottages and parkland containing dozens of tree species, and a rich diversity of birds and wildlife. Saskatchewan artists working in a variety of media have been inspired by the flora and fauna of these northern forests. Into the Woods features 12 artworks from the Saskatchewan Arts Board Permanent Collection that are inspired by the boreal forest and muskegs of northern Saskatchewan.

The Emma Lake Workshops, from 1955 to 2012, brought many local and international artists north to create art in directed workshops. Wynona Mulcaster and Ernest Linder both attended and mentored at the early Emma Lake Workshops. Mulcaster's Trees, painted in 1955, captures the density of the forest with an abstracted modernist style, layering blocks of monochromatic greens. She studied with Lindner, who had a cabin at Emma Lake. Lindner focused closely on the forest floor, often drawing or painting detailed bark, fallen trees and the mossy groundcover. Fifty years later Martha Cole applied this same scrutiny to her textile Scots Pine 2, bringing the tree trunk into sharp focus. Similar in composition to Lindner's Cedar Bark (1969), Cole combined digital printing on fabric with hand colouring and sewing to create the illusion of a realistic Scots Pine tree trunk.

In contrast, some artists choose instead to apply a more distanced view to their consideration of the forest. Sheila Archer's ceramic sculpture, Eye of the Muskeg, was inspired by aerial views of the rivers and forests of the north. Working for over 20 years as a canoe guide, Archer often traveled to work by float plane. Those flights highlighted the bold contrast between the structured geometry of the southern prairies and the river systems of the north. Increasing the distance even further and applying a geological aesthetic, Lorne Beug's ceramic sculpture, Earth Section with Trees, burrows deep into the earth to illustrate the forest's literal connection to the land. Beug uses unglazed multi-coloured clay for the layers of earth that contrasts with glossy glazed trees; the sculpture illustrates a dichotomy between the delicate chaos of nature and humanity's attempts to establish order and structure.

Boreal forests endure long winters with short growing seasons in boggy muskeg environments. The trees are often tall, thin, scraggly and scarred by forest fire. These forests look very different from the picturesque, chocolate boxesque, landscapes of historic European painting. Louise Cook and Hans Herold both capture the decaying forest within their painting practice, choosing to depict fallen and rotting trees, tangled brush and chaotic growth over a more romantic forest landscape. This unpicturesque perspective is utilized by Dave O'Hara through his “documentary” photography practice. O'Hara completed a series of photographs when living in La Loche in the late 1970s. He was particularly interested in documenting the hunting and trapping traditions of La Loche elder, Jonas Clark. Jonas and Beaverlodge, December 1979 captures the elder checking his traps in the winter, deep in the bush. Surrounded by trees, he is photographed with his tools as well as his crutch, which must have made trudging through the deep snow a challenge. These three artists subvert the picturesque to reflect the northern Saskatchewan landscape in its raw, rugged state.

Patuanak-born artist Catherine Blackburn utilizes Indigenous artforms in her art practice. As We Dance captures the Aurora Borealis skyscape above northern Saskatchewan's boreal forest using applied beadwork techniques. Taught to bead by her by close kin, Blackburn creates a unique view of the northern landscape. By incorporating a material and process historically used to adorn, she is asserting her connection to the land and claiming her place as an Indigenous artist within contemporary art practice.

Saskatchewan artists have used the trees themselves to create art. St. Brieux folk artist William Laczko carved sculptures for family and friends of birds and animals from found pieces of wood. Bird Tree combines a woodpecker and chicks, sparrow and crow together in one beguiling sculpture. Shell Lake landscape painter Rigmor Clarke often travels through the boreal forest, painting from her canoe. Inspired by the availability of willow, she taught herself how to weave baskets. Woven Basket was created in the early 1990s and was recently donated to the Permanent Collection. Also utilizing materials directly from the forest, Angelique Merasty harvested birch bark to create birch bark bitings, a traditional Indigenous skill she learned from her mother. Created by folding and biting thin sheets of birch bark to produce complex designs and patterns, Merasty was a master of her craft, known for her unique insect and animal patterns. These three artists' processes sensitively engage with nature by using wood.

Dating from 1954 to 2016, this exhibition from the SK Arts Permanent Collection includes painting, photography, basket weaving, birchbark biting, beadwork, and ceramic sculpture. As demonstrated by the artists included in this exhibition, vast, expansive prairie vistas are not the only landscapes prevalent in Saskatchewan. The northern boreal forest is an abstract, chaotic, mysterious and beautiful part of this province which provides not only sustenance to the people who live there, but also ample creative and artistic inspiration to Saskatchewan artists.

Artists include: Sheila Archer, Lorne Beug, Catherine Blackburn, Rigmor Clarke, Louise Cook, Hans Herold, Ernest Lindner, Angelique Merasty, Courtney Milne, Wynona Mulcaster and Dave O'Hara.

Belinda Harrow

Collections Consultant